A History of Locally Produced Food in Shoreline

By Brian Peterka © 2013 Diggin’ Shoreline

Introduction

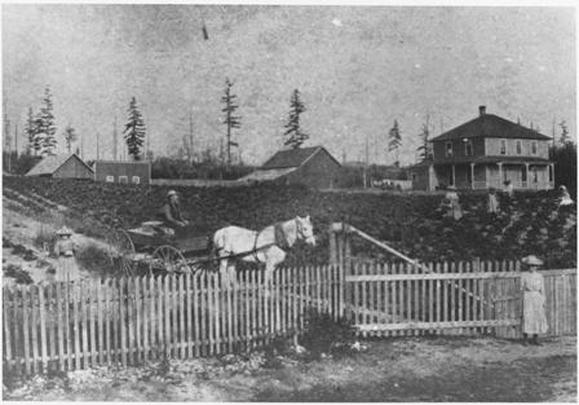

Carlson Family in their Potato Field, 1922 (Parkwood),

Photo #SHM 2018 courtesy of Shoreline Historical Museum

From the Native Americans who first inhabited the Shoreline area, to the pioneers who settled here in the late 19th century, to the urban farming movement of the 21st century, locally produced food has played an important role throughout the history of Shoreline, Washington. The berry farms, dairies, and chicken ranches of the early 20th century, the depression era “survival gardens” and wartime “victory gardens,” and the community gardens and farmers markets of today have all helped connect Shoreline residents to at least some of the sources of their food.

For the purposes of this article, “Shoreline” is used to describe what is now the City of Shoreline, but may also include parts of what is now the City of Lake Forest Park (LFP). Although “Shoreline” is used in the description of historical events throughout this article, much of the history described herein occurred before this area was actually known as “Shoreline.” For reference, Shoreline’s modern day neighborhood names have been included (in parentheses) throughout this article, although some of these neighborhood names were established after the historical events described. The term “garden” is used in this article to describe food gardens, as opposed to flower or other types of gardens.

Sidenote: Shoreline’s Name. The local school district chose the name “Shoreline” in the 1940s because it described the district’s extent from “shore to shore” (Lake Washington to Puget Sound) and “line to line” (Seattle City line to King / Snohomish County line). The City kept the name of “Shoreline” when it incorporated in 1995. [1]

For the purposes of this article, “Shoreline” is used to describe what is now the City of Shoreline, but may also include parts of what is now the City of Lake Forest Park (LFP). Although “Shoreline” is used in the description of historical events throughout this article, much of the history described herein occurred before this area was actually known as “Shoreline.” For reference, Shoreline’s modern day neighborhood names have been included (in parentheses) throughout this article, although some of these neighborhood names were established after the historical events described. The term “garden” is used in this article to describe food gardens, as opposed to flower or other types of gardens.

Sidenote: Shoreline’s Name. The local school district chose the name “Shoreline” in the 1940s because it described the district’s extent from “shore to shore” (Lake Washington to Puget Sound) and “line to line” (Seattle City line to King / Snohomish County line). The City kept the name of “Shoreline” when it incorporated in 1995. [1]

Early Inhabitants

Shoreline was inhabited by Duwamish groups long before the first Euro-American pioneers began arriving. An estimated 600 members of the Duwamish lived in Shoreline prior to the 1850s, and were supported by an abundant array of wild foods, including fish from the local rivers and lakes, shellfish and other seafood from the beaches and waters of the Puget Sound, game from the forests and marshes, and plants from the wetlands, forests, and meadows. [2]

Historical accounts indicate the local Duwamish people caught salmon and trout, dug clams and other shellfish, and hunted deer, elk, beaver, muskrat, martin, mink, otter, and waterfowl, including ducks. They also gathered fern rhizomes in the forest, skunk cabbages along Thornton Creek, picked crabapples at Bitter Lake (N. Seattle), salmon berries at the mouth of Boeing Creek (Innis Arden), cranberries at Ronald Bog (Meridian Park), and collected salal, red elderberries, kinnikinnick, and other native plants and berries that grew abundantly in the area. Obtaining food was an activity that likely occupied much of their daily lives. [3]

Sidenote: New Park, Old Name. One of Shoreline’s newest parks is located in a historic Duwamish plant gathering area along Richmond Beach. In recognition of the historical significance of the area, the City of Shoreline named the park “Kayu Kayu Ac,” which is a Northwest Native American Lushootseed term used to describe the Richmond Beach area as well as the native plant kinnikinnick or “Indian tobacco.” [4]

Historical accounts indicate the local Duwamish people caught salmon and trout, dug clams and other shellfish, and hunted deer, elk, beaver, muskrat, martin, mink, otter, and waterfowl, including ducks. They also gathered fern rhizomes in the forest, skunk cabbages along Thornton Creek, picked crabapples at Bitter Lake (N. Seattle), salmon berries at the mouth of Boeing Creek (Innis Arden), cranberries at Ronald Bog (Meridian Park), and collected salal, red elderberries, kinnikinnick, and other native plants and berries that grew abundantly in the area. Obtaining food was an activity that likely occupied much of their daily lives. [3]

Sidenote: New Park, Old Name. One of Shoreline’s newest parks is located in a historic Duwamish plant gathering area along Richmond Beach. In recognition of the historical significance of the area, the City of Shoreline named the park “Kayu Kayu Ac,” which is a Northwest Native American Lushootseed term used to describe the Richmond Beach area as well as the native plant kinnikinnick or “Indian tobacco.” [4]

Shoreline's First Gardeners

Carving out space to grow plants and attract wildlife is not a new concept. The Duwamish groups historically used controlled burning to create meadows in selected areas of the forest to cultivate edible plants, encourage the growth of berries, and to attract wild game. [5]

Two such areas were documented in the Shoreline area during U.S. government surveying activities in 1859. One was a several block-wide strip that spanned the entire length of Shoreline from north to south, roughly in line with what would eventually become Greenwood Avenue North. The other area of burned ground extended from this “Greenwood” burn area, to the east across Echo Lake to about where I-5 now runs, and north from about what is now Northeast 185th Street up to and beyond the city / county line at Northeast 205th Street. [6]

Two such areas were documented in the Shoreline area during U.S. government surveying activities in 1859. One was a several block-wide strip that spanned the entire length of Shoreline from north to south, roughly in line with what would eventually become Greenwood Avenue North. The other area of burned ground extended from this “Greenwood” burn area, to the east across Echo Lake to about where I-5 now runs, and north from about what is now Northeast 185th Street up to and beyond the city / county line at Northeast 205th Street. [6]

The Pioneers - Raising Food for Survival

Although non-native explorers, trappers, and traders passed through Shoreline for many years, the first permanent pioneer settlement in the area was the town of Richmond Beach, platted in 1890. The Great Northern Railroad was constructed through Richmond Beach in 1892, and the town began to grow. Many pioneers soon began immigrating to the area from the mid-western and eastern states. [7]

After finding a piece of property, a settler’s first tasks would be to cut down trees, blow up the stumps and clear part of the land to build a house, barn and chicken coop, dig a well, then clear more land for a garden and orchard. This is a recurring theme in the historical accounts of many pioneers in Shoreline. According to Richmond Beach resident Alford Anderson in a letter describing the ongoing land clearing activities in 1906, “the stumps are still flying like kites.” [8]

If folks produced more food than they could eat, they would preserve, barter or sell their bounty. There are several references in the historical record of early Shoreline residents canning, drying, smoking and storing their food. Historical accounts indicate that early settlers commonly traded vegetables for meat with the local butcher, traded eggs for groceries, sold vegetables to Native Americans passing through in canoes, and as overland routes improved, hauled their wares into Seattle by road to sell or trade for groceries, lumber, feed and other supplies. [9]

A garden and some livestock animals were often a settler’s direct link to survival, as well as a potential way to earn an income. As Shoreline’s communities became more established over time, many residents’ source of income was their employment, but they also raised fruit, berries, vegetables, and livestock as a way to stretch their income. [10]

After finding a piece of property, a settler’s first tasks would be to cut down trees, blow up the stumps and clear part of the land to build a house, barn and chicken coop, dig a well, then clear more land for a garden and orchard. This is a recurring theme in the historical accounts of many pioneers in Shoreline. According to Richmond Beach resident Alford Anderson in a letter describing the ongoing land clearing activities in 1906, “the stumps are still flying like kites.” [8]

If folks produced more food than they could eat, they would preserve, barter or sell their bounty. There are several references in the historical record of early Shoreline residents canning, drying, smoking and storing their food. Historical accounts indicate that early settlers commonly traded vegetables for meat with the local butcher, traded eggs for groceries, sold vegetables to Native Americans passing through in canoes, and as overland routes improved, hauled their wares into Seattle by road to sell or trade for groceries, lumber, feed and other supplies. [9]

A garden and some livestock animals were often a settler’s direct link to survival, as well as a potential way to earn an income. As Shoreline’s communities became more established over time, many residents’ source of income was their employment, but they also raised fruit, berries, vegetables, and livestock as a way to stretch their income. [10]

Fruits and VegetablesA wide variety of fruits and vegetables have been grown in Shoreline since the pioneers started gardening in the late 1800s. Fruits and vegetables specifically mentioned in Shoreline’s historical gardening records through the 1930s include apples, apricots, asparagus, beets, berries, cabbage, carrots, cauliflower, cherries, corn, cucumbers, grapes, hazelnuts, lettuce, nectarines, onions, parsnips, pears, peas, plums, potatoes, prunes, pumpkins, quinces, radishes, summer squash, string beans, tomatoes, and turnips. [11]

Sidenote: Seed Diversity. While most of the vegetables that were grown by the pioneers can still be found in gardens throughout Shoreline, many of the actual heirloom varieties that they grew likely no longer exist due to the estimated loss of up to 93% of food seed diversity over the past 100 years: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2011/07/food-ark/food-variety-graphic. Learn about one of the organizations that are working to increase seed diversity: http://www.seedalliance.org/Home/. Richmond Beach residents were enthusiastic fruit growers and produced enough fruit early in the town’s existence to make commercially viable shipments out of town, as evidenced by a 1901-1902 business directory which listed Richmond Beach’s export products as “fruit and lumber”. There was even an established fruit barrel-making business in the early days of Richmond Beach. [12] Prior to the construction of the Point Wells (Snohomish County) petroleum storage and distribution facility in 1912, Point Wells was the location of a large fruit farm owned by Billie Potts. [13] |

Family orchards were a ubiquitous feature on many properties in Shoreline in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Albert Caskey family operated a five acre fruit farm on Richmond Beach Road at 20th Avenue Northwest (Richmond Beach) in the 1920s and 1930s. The Henry Parry family had a five acre farm at Northwest 190th Street and 8th Avenue Northwest (Richmond Beach) in the 1890s and early 1900s with over 100 fruit trees. [14]

The first nursery in the area was the Richmond Nursery, which was established by Bill Adams in 1903 on five acres of land near what is now 8th Avenue Northwest and Richmond Beach Road (Hillwood). The nursery was known for its specially grafted fruit trees and rose bushes. There are also references to at least two garden nurseries started in the 1910s in what is now Lake Forest Park. [15]

One resident recollected of their childhood in Richmond Beach from 1903 to 1907: “It seemed like Heaven to us to have so much fruit and berries.” [16]

Sidenote: Historical Orchards. Many of the early farms in Shoreline were built on lots that were at least five acres in size. As development pressures increased over time, these larger lots were subdivided into smaller and smaller lots. Over time, the fruit trees on large orchards often became split up among several smaller lots, and their histories eventually forgotten. Now fast forward to our time. Many of these historic fruit trees may still exist in back yards around Shoreline. In some cases, the surviving fruit trees may now be rare varieties. [17]

People without prior gardening experience learned from others and/or by trial and error. In the early 1910s, Northwest newspapers began publishing information on gardening, including prevention of insect and disease damage. Prospective farmers could also learn about farming and raising chickens at nearby Alderwood Manor (now part of Lynnwood), which operated a 30-acre demonstration farm, including a chick hatchery, gardens and orchards. This local educational facility trained agricultural entrepreneurs during the 1920s, but closed in the 1930s due to the effects of the Great Depression. [18]

The first nursery in the area was the Richmond Nursery, which was established by Bill Adams in 1903 on five acres of land near what is now 8th Avenue Northwest and Richmond Beach Road (Hillwood). The nursery was known for its specially grafted fruit trees and rose bushes. There are also references to at least two garden nurseries started in the 1910s in what is now Lake Forest Park. [15]

One resident recollected of their childhood in Richmond Beach from 1903 to 1907: “It seemed like Heaven to us to have so much fruit and berries.” [16]

Sidenote: Historical Orchards. Many of the early farms in Shoreline were built on lots that were at least five acres in size. As development pressures increased over time, these larger lots were subdivided into smaller and smaller lots. Over time, the fruit trees on large orchards often became split up among several smaller lots, and their histories eventually forgotten. Now fast forward to our time. Many of these historic fruit trees may still exist in back yards around Shoreline. In some cases, the surviving fruit trees may now be rare varieties. [17]

People without prior gardening experience learned from others and/or by trial and error. In the early 1910s, Northwest newspapers began publishing information on gardening, including prevention of insect and disease damage. Prospective farmers could also learn about farming and raising chickens at nearby Alderwood Manor (now part of Lynnwood), which operated a 30-acre demonstration farm, including a chick hatchery, gardens and orchards. This local educational facility trained agricultural entrepreneurs during the 1920s, but closed in the 1930s due to the effects of the Great Depression. [18]

Cultivated Berries

Morten Anderson Strawberry Farm, 1910 (Richmond Beach), Photo #SHM 1615 courtesy of Shoreline Historical Museum

Cultivated berries historically grown in Shoreline include blueberries, currants, gooseberries, loganberries, Olympic berries (early cross between the loganberry and the black raspberry), raspberries, and most significantly, strawberries. Strawberries were a very important part of the settler’s lives from the 1890s into the 1910s, and Richmond Beach became widely known in those days as a strawberry raising community. There were several strawberry farms located in Richmond Beach, and during vacation, most of the children in the community picked strawberries. Sometimes, school was even dismissed early in the year so the kids could help to harvest the crop. [19]

By 1906, Richmond Beach’s strawberries, which mostly consisted of the Marshall variety, were considered to be some of the best to reach Seattle’s berry market. Richmond Beach fruit and berry farmer Henry Parry cultivated a new variety of strawberry in the early 1900s and named it the Richmond Beauty. This berry became famous for its good flavor and tremendous size; only three or four berries could fit into a box. The Richmond Beauty won prizes at the Puyallup Fair and at the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition in Seattle, which brought a lot of publicity to Richmond Beach. [20]

Berries were shipped from Richmond Beach by road or rail to markets in Seattle, Edmonds, Everett, and beyond. One historical reference indicates that about 10,000 crates of berries were being shipped annually from the Richmond Beach depot. In the early 1900s, farmers who sold their berries in Seattle would reportedly hitch up their horse and wagon and leave around 1:00 am to arrive at the commission houses on Western Avenue by 5:00 or 6:00 am. Once the berries were sold, the farmer would have breakfast and head back to Richmond Beach, arriving in the early afternoon to pick berries in preparation for the next day’s trip back to Seattle. This routine would continue throughout the summer berry season. [21]

A strawberry blight apparently ended commercial strawberry growing operations in Shoreline in the mid 1910s. [22]

Sidenote: Strawberry Festival. Even though Shoreline’s strawberry farms have been gone for a century, the Richmond Beach community still celebrates their flavorful past with an annual Strawberry Festival: http://www.richmondbeachwa.org/strawberryfestival/.

By 1906, Richmond Beach’s strawberries, which mostly consisted of the Marshall variety, were considered to be some of the best to reach Seattle’s berry market. Richmond Beach fruit and berry farmer Henry Parry cultivated a new variety of strawberry in the early 1900s and named it the Richmond Beauty. This berry became famous for its good flavor and tremendous size; only three or four berries could fit into a box. The Richmond Beauty won prizes at the Puyallup Fair and at the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition in Seattle, which brought a lot of publicity to Richmond Beach. [20]

Berries were shipped from Richmond Beach by road or rail to markets in Seattle, Edmonds, Everett, and beyond. One historical reference indicates that about 10,000 crates of berries were being shipped annually from the Richmond Beach depot. In the early 1900s, farmers who sold their berries in Seattle would reportedly hitch up their horse and wagon and leave around 1:00 am to arrive at the commission houses on Western Avenue by 5:00 or 6:00 am. Once the berries were sold, the farmer would have breakfast and head back to Richmond Beach, arriving in the early afternoon to pick berries in preparation for the next day’s trip back to Seattle. This routine would continue throughout the summer berry season. [21]

A strawberry blight apparently ended commercial strawberry growing operations in Shoreline in the mid 1910s. [22]

Sidenote: Strawberry Festival. Even though Shoreline’s strawberry farms have been gone for a century, the Richmond Beach community still celebrates their flavorful past with an annual Strawberry Festival: http://www.richmondbeachwa.org/strawberryfestival/.

Livestock

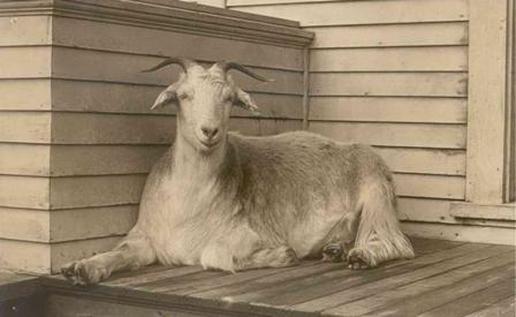

Mrs. McGinnis’ Goat, 1912 (Richmond Highlands), Photo #SHM 554 courtesy of Shoreline Historical Museum

Barbara Bender, author of “Growing Up With Lake Forest Park,” helps us imagine what life in this area was like back in the 1910s and 1920s: “Livestock and gardens contributed to rural sounds and smells which the country-raised individual remembers so keenly. As a child, recuperating in bed one spring, I recall listening attentively to every sound and savoring every odor reaching me from the open window. I remember how the muted crowing of distant roosters differed markedly from the singing of nearby birds, and how the gentle ‘moo’ of our family cow compared with the occasional soft bark of resident chipmunks. I can still experience the tantalizing fragrance of lilac, mock-orange, or apple blossoms, in sharp contrast to the earthy effluvium of cow barn, pig pen and chicken coop, but each is remembered with equal nostalgia.” [23]

Based on the historical record, raising livestock was a common practice in the early days of Shoreline. Many folks raised their own chickens, cows, ducks, geese, goats, hogs, rabbits, squabs (pigeons / doves), and turkeys. Manure from livestock was used to fertilize the soil, which benefited the fruits and vegetables. [24]

Some particular farm animals were even well known around town. Around 1912, Mrs. McGinnis’ goat was a regular fixture on the porch of the Ronald Methodist Church (Richmond Highlands), and also at the nearby Ronald School (now part of Shorewood High School). As the story goes, the school kids would often feed the goat out in the schoolyard. One time when the kids were in class, the goat ventured into the school building, got into the coat closet, and proceeded to eat the children’s lunches being stored there. At lunchtime, the goat was discovered and taken back home, and Mrs. McGinnis saved the day by making peanut butter sandwiches for all of the kids. [25]

Based on the historical record, raising livestock was a common practice in the early days of Shoreline. Many folks raised their own chickens, cows, ducks, geese, goats, hogs, rabbits, squabs (pigeons / doves), and turkeys. Manure from livestock was used to fertilize the soil, which benefited the fruits and vegetables. [24]

Some particular farm animals were even well known around town. Around 1912, Mrs. McGinnis’ goat was a regular fixture on the porch of the Ronald Methodist Church (Richmond Highlands), and also at the nearby Ronald School (now part of Shorewood High School). As the story goes, the school kids would often feed the goat out in the schoolyard. One time when the kids were in class, the goat ventured into the school building, got into the coat closet, and proceeded to eat the children’s lunches being stored there. At lunchtime, the goat was discovered and taken back home, and Mrs. McGinnis saved the day by making peanut butter sandwiches for all of the kids. [25]

Cows

Before beef, milk, cream, butter and cheese were widely available commercially, many settlers raised their own cows for dairy and meat. Before there were any pasture laws, their cows were allowed to wander loose to graze around Richmond Beach, and beyond. [26]

Prior to the construction of the Point Wells (Snohomish County) petroleum storage and distribution facility in 1912, the large fruit farm at Point Wells also had a resident herd of cattle. Point Wells was a magnet for other local cows too because it was covered with fine grass on which the cows liked to graze. Each evening, folks from Richmond Beach reportedly would walk along the railroad tracks out to Point Wells to bring their cows back home. [27]

The first licensed dairy in the area was started in the early 1900s by Mr. and Mrs. Hans Johnson on their former strawberry farm in Richmond Beach along what is now 15th Avenue Northwest. In 1922 the Richmond Highlands Dairy Farm was started by Sam Christianson in the Richmond Highlands area. This dairy started with six cows and delivered 60 quarts of raw and pasteurized milk and cream each day. The operation had expanded and moved to Bothell by the 1930s, and was producing over 1,000 quarts of milk per day. [28]

If you wanted to take a cow to market in the 1890s and early 1900s, this could mean physically walking the cow from Shoreline all the way to Ballard! [29]

Prior to the construction of the Point Wells (Snohomish County) petroleum storage and distribution facility in 1912, the large fruit farm at Point Wells also had a resident herd of cattle. Point Wells was a magnet for other local cows too because it was covered with fine grass on which the cows liked to graze. Each evening, folks from Richmond Beach reportedly would walk along the railroad tracks out to Point Wells to bring their cows back home. [27]

The first licensed dairy in the area was started in the early 1900s by Mr. and Mrs. Hans Johnson on their former strawberry farm in Richmond Beach along what is now 15th Avenue Northwest. In 1922 the Richmond Highlands Dairy Farm was started by Sam Christianson in the Richmond Highlands area. This dairy started with six cows and delivered 60 quarts of raw and pasteurized milk and cream each day. The operation had expanded and moved to Bothell by the 1930s, and was producing over 1,000 quarts of milk per day. [28]

If you wanted to take a cow to market in the 1890s and early 1900s, this could mean physically walking the cow from Shoreline all the way to Ballard! [29]

Hogs

Hogs were raised for meat, but just as importantly, they were widely used as the way to dispose of food wastes in the days before garbage collection services. Many settlers in Shoreline kept their own hogs. There were also several historic hog farms in Shoreline, including at the Firland Sanatorium at Fremont Avenue North and North 195th Street (Hillwood) circa 1930s. The area currently occupied by the bowling alley on Richmond Beach Road near 15th Avenue Northwest (Richmond Beach) was the location of a hog farm operated by Mikel Lund in the late 1890s to early1900s. That area was historically known as “Lard Valley.” [30]

Chickens

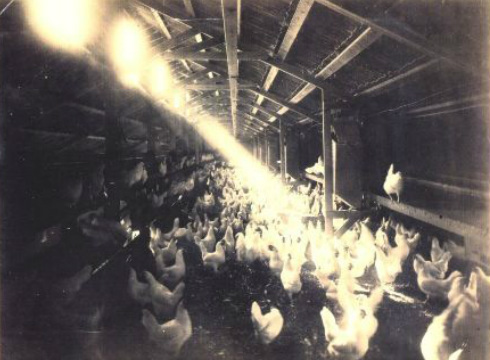

|

Many settlers in Shoreline raised chickens for eggs and meat for personal consumption. Around 1909, there was a big promotion to raise chickens for the meat and egg market, and many folks in Shoreline soon began making their living by raising poultry. During the 1920s, many people wanted to get out of Seattle and have their own idyllic “little place in the country,” where they could live off of the land and/or an income from raising chickens. For many, living out the “American dream” in this way did not turn out to be a realistic or sustainable venture. The egg and poultry markets were hit hard by the Great Depression (1930-mid 1940s), and many chicken farms went out of business. [31]

Raising chickens and other livestock in Shoreline could be challenging due to predators, weather, disease, and other factors. Local predators mentioned in historical accounts include black bears, bobcats, cougars, raccoons, skunks, and even thieves. One Richmond Beach resident recollected of the 1920s, “It was also a time for chicken thieves. Barely a week went by but what someone had chickens stolen.” [32] Emma Muller raised 2,000 chickens with her husband Arthur in Lake Forest Park in the 1920s. Arthur had made an agreement with the Lake Forest Park School Board in 1921 to purchase a truck to transport school children under the condition that he could also transport crates of eggs under the children’s seats. Emma recollected that “the winter of 1923-1924 was bad for the chicken business; many died of disease, so that was the end of chickens in our life.” After their chicken business failed, Arthur continued on as the school bus driver for seven more years. [33] One Shoreline chicken farm on Dayton Avenue near Northeast 173rd Street (Richmond Highlands), operated by Morton Clark in the 1910s / 1920s, went out of business after a delivery of tainted feed caused the death of all 5,000 of his hens. Morton sued the feed company for damages, but an appeals judge subsequently (and mysteriously) overturned the initial order for restitution. [34] The Anthony Electric Farm operated on Richmond Beach Road at 3rd Avenue Northwest (Hillwood) during the 1920s. The chicken farm and chick hatching plant included an electric incubator with a 30,000 egg capacity. They also manufactured and sold egg incubator equipment. As the cost of feed increased and the demand for poultry decreased, the farm was converted to a manufacturing-only facility. [35] |

|

The Fish Brother’s Queen City Poultry Ranch operated on ten acres at North 158th Street and Greenwood Avenue North (Highland Terrace). Historical marketing documents indicate that the ranch had over 4,000 laying hens in the mid 1920s. The farm was also a popular weekend tourist attraction, and visitors reportedly were astounded by its automated hen feeding and egg cleaning equipment. The ranch was in business from 1906 until the 1940s, by which time the chicken industry was moving toward mass production, and chicken yards were being replaced by cages. [36]

There are also historical references to several other chicken farms in the Shoreline area, including at least ten chicken farms in the 1900s to 1930s located in what is now Lake Forest Park. [37]

Sidenote: Farm Animals Today. Over a century later and it’s still legal in Shoreline to raise some of the smaller “farm-type” animals in your own back yard, including chickens, goats, rabbits and honeybees. For more information, check out the Shoreline Municipal Code (20.40.240 Animals): http://www.codepublishing.com/wa/shoreline/?Shoreline20/Shoreline20.html.

There are also historical references to several other chicken farms in the Shoreline area, including at least ten chicken farms in the 1900s to 1930s located in what is now Lake Forest Park. [37]

Sidenote: Farm Animals Today. Over a century later and it’s still legal in Shoreline to raise some of the smaller “farm-type” animals in your own back yard, including chickens, goats, rabbits and honeybees. For more information, check out the Shoreline Municipal Code (20.40.240 Animals): http://www.codepublishing.com/wa/shoreline/?Shoreline20/Shoreline20.html.

Wild Foods

There are many accounts of early settlers foraging, fishing and hunting in Shoreline, just as the Duwamish had done before them. There is even one historical reference to pioneers planting white clover in logged areas in the 1890s, which not only provided food for their cows, but also gave everyone “more wild honey.” [38]

Ronald Bog (Meridian Park) continued to be the place to go for wild cranberries, and it had also become a popular picnic destination by the early 1900s. One account from 1902 indicates that the trail to the bog was rough and winding, the cranberries were small but plentiful, and deer, bear and grouse were always present. [39]

Salmon berries and red huckleberries grew in the woods and swamps. The sand and gravel pit (now the Richmond Beach Saltwater Park) was a popular destination for picking native blackberries in the early days. Native blackberries were abundant throughout the area, as were the black bears that liked to eat them. [40]

Ronald Bog (Meridian Park) continued to be the place to go for wild cranberries, and it had also become a popular picnic destination by the early 1900s. One account from 1902 indicates that the trail to the bog was rough and winding, the cranberries were small but plentiful, and deer, bear and grouse were always present. [39]

Salmon berries and red huckleberries grew in the woods and swamps. The sand and gravel pit (now the Richmond Beach Saltwater Park) was a popular destination for picking native blackberries in the early days. Native blackberries were abundant throughout the area, as were the black bears that liked to eat them. [40]

Fish and Game

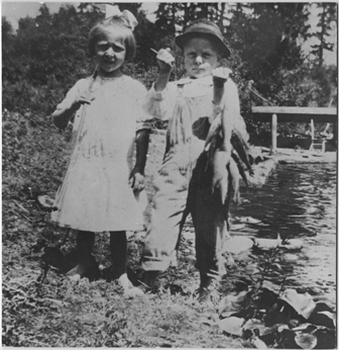

|

The Puget Sound provided a wonderful array of food, including bottom fish, crabs, flounder, halibut, and salmon. Big Rock Cod could be caught from the dock at the sand and gravel pit (Richmond Beach); Deep Sea Sole – “more than we could eat” could be caught from a row boat off of Point Wells; clams were plentiful and could be “picked right off the beach” at Point Wells at low tide. [41]

Prior to 1908, Shoreline was known as a hunter’s and fisherman’s paradise. The woods were full of black bear and deer “all the way across to Lake Washington.” Deer flourished around Hidden Lake (Innis Arden), and elk, geese, grouse, pheasant, and quail were plentiful. Historically, both trout and salmon would fill up the small creeks from Lake Washington, like McAleer Creek (Ballinger / LFP) and Lyons Creek (LFP), solid from shore to shore, and stories of catching a hundred or more within an hour were common. There were trout in Echo Lake. Hidden Lake was “alive with trout.” Boeing Creek, also known as Hidden Creek (Innis Arden), was a “fisherman’s dream come true.” [42] A fish trap, which extended 1,000 feet into Puget Sound, was built in 1903 to catch salmon at Point Wells (Snohomish County), and a second fish trap was constructed four or five miles south of Richmond Beach. At one time, there was a fish cannery operating out of the former sand and gravel company buildings on Richmond Beach. The Boeing Family and King County (circa 1916) each operated a fish hatchery at different times on Boeing Creek (Innis Arden). [43] |

By 1910, the Seattle-Everett Interurban Electric Line was completed (now the Interurban Trail), and on Sundays its cars would be filled with hunters, guns, and dogs heading to Shoreline. Its cars looked like “an army train going to battle.” Recreational hunters, who were historically seldom seen in Shoreline before that time, could be seen “anytime and anywhere.” The hunting and fishing in Shoreline which had been so good for so long was soon virtually eliminated. [44]

Black bears continued to live in Shoreline for many years, even as development was increasing. Some construction workers building houses in the Ridgecrest neighborhood in the late 1940s reportedly carried pistols while they worked because of the numerous black bears in the area. [45]

Sidenote: Bear Sightings. The last bear sightings in Shoreline were in 2009 when a young black bear wandered through town on its way northeast from the Ballard area. It was spotted in Shoreline several times, including in Twin Ponds Park (Parkwood) and on the running track at Kellogg Middle School (North City). The bear even rummaged through one resident’s backyard honeybee hives in the Ridgecrest neighborhood along the way. [46]

Black bears continued to live in Shoreline for many years, even as development was increasing. Some construction workers building houses in the Ridgecrest neighborhood in the late 1940s reportedly carried pistols while they worked because of the numerous black bears in the area. [45]

Sidenote: Bear Sightings. The last bear sightings in Shoreline were in 2009 when a young black bear wandered through town on its way northeast from the Ballard area. It was spotted in Shoreline several times, including in Twin Ponds Park (Parkwood) and on the running track at Kellogg Middle School (North City). The bear even rummaged through one resident’s backyard honeybee hives in the Ridgecrest neighborhood along the way. [46]

Depression and War Era Gardens

The “war garden” campaign was launched by the National War Garden Commission during World War I (1914-1918). This program got people growing vegetables, fruits and herbs in their own yards, on vacant lots, in school yards, and in parks and other public spaces to reduce the pressure on the food supply during the war. It is estimated that in the United States over five million war gardens were planted during World War I. [47]

Although national interest in gardening generally declined with the end of World War I and the war garden campaign, many folks did continue to keep a garden. According to one historical account of the 1920s by Shoreline (Parkwood) residents Clint Staaf and Syrene Forsman, “Most folks around here had sizeable vegetable gardens.” [48]

Although national interest in gardening generally declined with the end of World War I and the war garden campaign, many folks did continue to keep a garden. According to one historical account of the 1920s by Shoreline (Parkwood) residents Clint Staaf and Syrene Forsman, “Most folks around here had sizeable vegetable gardens.” [48]

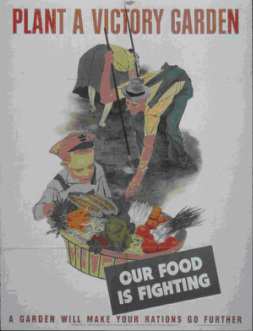

WWII Victory Garden Poster

During the Great Depression (1930-mid 1940s) many folks in Shoreline were once again gardening for survival, like the pioneers and early settlers had done decades before them. Many of these depression era gardens continued right on through as “victory gardens” during World War II (1939-1945). [49]

Like the “war garden” campaign of World War I, the “victory garden” was a government campaign meant to boost national food production, as well as morale. Such ultra-local food production minimized impacts to the labor, transportation and distribution resources which were already being overextended by the war. It is estimated that in the United States over 20 million victory gardens were planted during World War II, and these supplied 44% of the country’s produce. [50]

The following oral histories describe gardening activities in Shoreline during the Great Depression and World War II.

Longtime Shoreline (Hillwood) resident Helen Cox Oltman, born in 1924: “We almost always had a garden when I was a child - we didn’t really call it anything - a survival garden, I guess! We shared with people who didn’t have any, and nearly all the neighbors seemed to have some kind of a garden. I suppose after the war started that we called it a ’victory garden’ like everybody else, but since we were used to having a garden, we didn’t need to change what we were doing.” [51]

Longtime Shoreline (Meridian Park) resident Bruce Adams, born in 1933: “There was a lot of poor people out here then in the early 1940s - they’d lost everything in the Great Depression. They came out here and bought a lot for $10 down, and put up a camp on it, or maybe a one room shack until they saved enough money to build a house. The people next door to us did that. They and their kids lived in a tent to start with, then eventually built a house. When the war came along, everyone had a victory garden, if they didn’t already have a garden to start with. Most folks did anyway, for survival. The ones who already had gardens just started calling theirs ‘victory gardens’ because that was a way of participating.” [52]

Like the “war garden” campaign of World War I, the “victory garden” was a government campaign meant to boost national food production, as well as morale. Such ultra-local food production minimized impacts to the labor, transportation and distribution resources which were already being overextended by the war. It is estimated that in the United States over 20 million victory gardens were planted during World War II, and these supplied 44% of the country’s produce. [50]

The following oral histories describe gardening activities in Shoreline during the Great Depression and World War II.

Longtime Shoreline (Hillwood) resident Helen Cox Oltman, born in 1924: “We almost always had a garden when I was a child - we didn’t really call it anything - a survival garden, I guess! We shared with people who didn’t have any, and nearly all the neighbors seemed to have some kind of a garden. I suppose after the war started that we called it a ’victory garden’ like everybody else, but since we were used to having a garden, we didn’t need to change what we were doing.” [51]

Longtime Shoreline (Meridian Park) resident Bruce Adams, born in 1933: “There was a lot of poor people out here then in the early 1940s - they’d lost everything in the Great Depression. They came out here and bought a lot for $10 down, and put up a camp on it, or maybe a one room shack until they saved enough money to build a house. The people next door to us did that. They and their kids lived in a tent to start with, then eventually built a house. When the war came along, everyone had a victory garden, if they didn’t already have a garden to start with. Most folks did anyway, for survival. The ones who already had gardens just started calling theirs ‘victory gardens’ because that was a way of participating.” [52]

The Latter Half of the 20th Century

American’s interest in gardening declined again after World War II. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, about 39% of the population lived on farms in 1900, compared to about 16% in 1950, and less than 2% in 1990, and consumption of home-produced vegetables declined from 131 pounds per person in 1909, to just 11 pounds in 1998. [53]

Suburban areas, including Shoreline, experienced rapid growth after World War II. Reliance on local food production diminished as food processing, packaging and distribution systems were refined. Refrigeration made it possible to store food longer. Interstate 5 was completed through Shoreline in the early 1960s, and through the rest of Washington by the end of that decade, making it possible for food to be trucked in from further and further away. Supermarkets and fast food restaurants were on the rise. Television advertisements had people humming catchy food product jingles. Convenience foods and microwave ovens became widely available. People’s lives were getting busier. [54]

In the early 1970s, the greater Seattle area was reeling from a national energy crisis and mass layoffs at Boeing. Unemployment rose to 17% locally and many people didn’t have enough money for food. Social activism was on the rise. The “back to the land movement” of the 1960s / 1970s was well underway, drawing folks from cities around the U.S. to more “alternative” rural and agricultural lifestyles. [55]

As the trend goes, gardening activity increases when times get tough. The Seattle P-Patch Program was formed, and opened its first community garden in Seattle in 1973. For a small plot fee, people could grow food at the community garden for themselves and for those in need. The program is named in part after its first community garden location. The “P” in P-Patch stands for Piccardo, the family who previously owned and farmed the land before it became a community garden. The term “P-Patch” is now used by community gardens around the country. [56]

The Seattle Tilth, whose mission includes building an equitable and sustainable local food system, had its beginnings in 1974 after its founders were inspired by a speech by the poet / farmer / philosopher Wendell Berry. Berry reportedly linked the "drastic decline in the farm population" with "the growth of a vast, uprooted, dependent and unhappy urban population." [57]

Sidenote: Local Gardening Guide. The Seattle Tilth’s Maritime Northwest Garden Guide is an excellent resource for vegetable, herb and flower gardening in our area, with month-by-month planting and maintenance information: http://seattletilth.org/get-involved/buystuff.

Suburban areas, including Shoreline, experienced rapid growth after World War II. Reliance on local food production diminished as food processing, packaging and distribution systems were refined. Refrigeration made it possible to store food longer. Interstate 5 was completed through Shoreline in the early 1960s, and through the rest of Washington by the end of that decade, making it possible for food to be trucked in from further and further away. Supermarkets and fast food restaurants were on the rise. Television advertisements had people humming catchy food product jingles. Convenience foods and microwave ovens became widely available. People’s lives were getting busier. [54]

In the early 1970s, the greater Seattle area was reeling from a national energy crisis and mass layoffs at Boeing. Unemployment rose to 17% locally and many people didn’t have enough money for food. Social activism was on the rise. The “back to the land movement” of the 1960s / 1970s was well underway, drawing folks from cities around the U.S. to more “alternative” rural and agricultural lifestyles. [55]

As the trend goes, gardening activity increases when times get tough. The Seattle P-Patch Program was formed, and opened its first community garden in Seattle in 1973. For a small plot fee, people could grow food at the community garden for themselves and for those in need. The program is named in part after its first community garden location. The “P” in P-Patch stands for Piccardo, the family who previously owned and farmed the land before it became a community garden. The term “P-Patch” is now used by community gardens around the country. [56]

The Seattle Tilth, whose mission includes building an equitable and sustainable local food system, had its beginnings in 1974 after its founders were inspired by a speech by the poet / farmer / philosopher Wendell Berry. Berry reportedly linked the "drastic decline in the farm population" with "the growth of a vast, uprooted, dependent and unhappy urban population." [57]

Sidenote: Local Gardening Guide. The Seattle Tilth’s Maritime Northwest Garden Guide is an excellent resource for vegetable, herb and flower gardening in our area, with month-by-month planting and maintenance information: http://seattletilth.org/get-involved/buystuff.

Into the 21st CenturyWith the housing market crash of 2008 and the resulting economic recession came another resurgence of interest in gardening and locally produced food. There were rising national concerns about how food was being produced, how far it was traveling, and about food safety credibility with food being shipped from unknown sources. “Urban farming” and “local food” movements were soon in full swing. Whereas the “back to the land” movements of the past included a migration from cities to more rural areas, this “urban farming” movement focused on small-scale agriculture within the city. [58]

Garden beds became a familiar sight in yards around Shoreline. Chicken coops and honeybee hives began cropping up around town. Some residents pulled out their lawns and dedicated most or all of their yard space to raising food. Recurring neighborhood bartering parties were established to provide opportunities for people to trade their garden produce, home-canned goods, and other wares. [59] Sidenote: Co-op for Urban Farmers. The Seattle Farm Co-op is a community-based project started in 2009 which supplies urban farmers with animal feed, fertilizers, mulch, seeds, etc., many from local and sustainable sources. They also have an active online community: http://www.seattlefarmcoop.com/. Several community and educational garden projects were developed in Shoreline around this time, including:

Diggin’ Shoreline was formed by a group of gardeners, urban farmers, and community activists in 2009 to promote community gardens and a sustainable food system in Shoreline. Diggin’ Shoreline hosts gardening classes and other educational opportunities for the community, and has helped in the development of several gardens, including:

Several other community garden projects are also underway. Many of Shoreline’s community gardens also grow food for local food banks. As of 2012, the Seattle P-Patch Program had 78 community gardens serving 4,400 gardeners, with over 1,000 people on its waiting list with up to a four year wait for a garden plot. Some Shoreline residents have even been on the waiting list for a garden plot in Seattle because they had no place to garden in Shoreline. [62] Sidenote: Gardening in the Right-of-Way. To support residents’ interest in gardening, the City of Shoreline has simplified its notification process and removed the permit fee for certain types of plantings in the “parking strip” and other City right-of-ways. See the City’s “Planting in the Right-of-Way” information at: http://www.shorelinewa.gov/index.aspx?page=571. |

Neighborhood farmers markets, which have been increasing in number around the Seattle area since the 1990s, have also become established in our area. The Lake Forest Park Farmers Market started up in 1995, and the Shoreline Farmers Market opened in 2012. Both markets celebrate locally produced food and other goods by hosting a variety of local farmers and producers, artisans, food vendors and musicians. [63]

Sidenote: Local Farmers Markets. For ore info on our local farmers markets: Shoreline Farmers Market: http://www.shorelinefarmersmarket.org/.

Lake Forest Park Farmers Market: http://www.thirdplacecommons.org/farmersmarket/.

Sidenote: Local Farmers Markets. For ore info on our local farmers markets: Shoreline Farmers Market: http://www.shorelinefarmersmarket.org/.

Lake Forest Park Farmers Market: http://www.thirdplacecommons.org/farmersmarket/.

Where To Go From Here

If you haven’t already tried it…..start a simple garden of your own, or try container gardening on your porch. Go over and meet that neighbor with the chickens. Pick those blackberries on the corner lot. Meet the farmers and producers at the local farmers markets. Get involved with your gardening community. Support the local school garden. Sign up for a plot at a community garden, or find out how to get one started in your neighborhood.

By having a more personal connection to our food, we follow in the footsteps of the Duwamish, the 19th century pioneers, and others who have created this history of locally produced food in Shoreline.

By having a more personal connection to our food, we follow in the footsteps of the Duwamish, the 19th century pioneers, and others who have created this history of locally produced food in Shoreline.

Do You Have a Story to Share?

Please submit your stories or information, recent or historical, about locally produced food in the Shoreline area to [email protected].

Notes

Special thanks to Vicki Stiles of the Shoreline Historical Museum.

- City of Shoreline, “Shoreline History,” http://www.cityofshoreline.com/index.aspx?page=45 (accessed December 13, 2012).

- David Buerge, “The Maps of the Early Shoreline Area,” for the Shoreline Historical Museum, unpublished manuscript, 1996, p. 2.

- Buerge, “The Maps of the Early Shoreline Area,” pp. 2, 3, 6-10.

- City of Shoreline, “Kayu Kayu Ac Park,” http://www.cityofshoreline.com/index.aspx?page=161 (accessed December 12, 2012).

Buerge, “The Maps of the Early Shoreline Area,” p. 2. - Buerge, “The Maps of the Early Shoreline Area,” pp. 3-6.

- Buerge, “The Maps of the Early Shoreline Area,” pp. 5-6.

Author’s estimates based on Shoreline Historical Museum exhibit map, “Shoreline Environment 1859.” - Vicki Stiles - Shoreline Historical Museum, personal communication to author, December 11, 2012.

- Ruth Worthley, ed., Shoreline Memories, Volume 1 (Shoreline: Shoreline Historical Society, 1973), pp. 3, 20, 23, 50, 65, 68, 107.

Ruth Worthley, ed., Shoreline Memories, Volume 2 (Shoreline: Shoreline Historical Society, 1975), pp. 9, 10, 14, 38, 40, 74, 76. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 17, 25, 47, 81, 116, 117.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 17, 18, 76.

Barbara L. Drake Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park – The Early Decades in “North Seattle,” (Edmonds: Creative Communications, 1983), pp. 259, 260. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 20, 21, 68.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, p. 228. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 20, 21, 25, 28, 47, 48, 50, 51, 63, 65, 68, 81, 83, 89.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 4, 17, 18, 24, 34, 39, 74.

George Cooper, “Highland Fall Show Successful,” Richmond Beach Herald, September 25, 1925, p. 1.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, p. 258-260. - R.L. Polk & Company, Oregon, Washington and Alaska Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1902-1902, p. 626

Vicki Stiles - Shoreline Historical Museum, verbal communication to author, January 17, 2013. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, p. 89.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 15-18, 74.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 91-92.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 4, 66-67.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 259. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, p. 51.

- Kathy Mendelson - Pacific Northwest Garden History website, e-mail message to author, October 21, 2012.

- Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, p. 258.

Alderwood History, Alderwood Manor Heritage Association, http://www.alderwood.org/history.html (accessed January 8, 2013). - George Cooper, “Highland Fall Show Successful,” Richmond Beach Herald, September 25, 1925.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 17, 20-22, 24, 28-30, 40, 48, 49, 51, 63, 64, 68, 76, 77, 81, 83.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 4, 17, 43, 74, 76, 79.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 259, 260. - “Lake Berries are Finished,” Seattle Times, June 8, 1906.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 74. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, p. 29, 76.

“Richmond Beach” listing in R.L. Polk & Company’s King County Directory, 1911-1912. - Vicki Stiles - Shoreline Historical Museum, verbal communication to author, November 7, 2012.

- Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, p. 260.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 17, 21, 31, 40, 42, 47, 48, 51, 68, 83, 85, 89, 128.[1]. City of Shoreline, “Shoreline History,” http://www.cityofshoreline.com/index.aspx?page=45 (accessed December 13, 2012).

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 5, 11, 15, 17, 18, 23, 24, 30-33, 39, 43, 62, 68, 73, 76, 79.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 258-260. - Vicki Stiles - Shoreline Historical Museum, verbal communication to author, October 25, 2012.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 17, 31, 40, 47, 48, 51, 68, 89, 128.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, p. 5, 11, 17, 23, 24, 33, 43, 68, 79.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 258-260. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 31, 48, 89.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, p. 40.

“Good Milk from a Great Farm,” Bothell Citizen, May 4, 1938. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, p. 47.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 47, 68.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 39, 72, 73.

Photo - “Firland Sanatorium and hog farm, Shoreline, November 21, 1934,” University Libraries Digital Collections, University of Washington, http://content.lib.washington.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/fera&CISOPTR=251&CISOBOX=1&REC=1 (accessed January 5, 2013).

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 259, 260. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 17, 21, 42, 47, 68, 83.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 15, 17, 23, 30-33, 39, 62, 76, 79.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 258-260.

Vicki Stiles - Shoreline Historical Museum, verbal communication to author, December 11, 2012.

Alderwood History, Alderwood Manor Heritage Association, http://www.alderwood.org/history.html (accessed January 8, 2013). - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 13, 58, 68, 70, 83, 91, 116, 118.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 20, 44.

“Bears Fattening on Chickens,” Seattle Times, July 10, 1906. - Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, p. 258.

- Morton Clark Jr., e-mail message to Vicki Stiles - Shoreline Historical Museum, December 21, 2012.

- Undated historical documents, Shoreline Historical Museum’s “Anthony Electric Farm” and “Richmond Manufacturing” files.

- Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 30-33.

Fish Bros. marketing brochure, 1924, in Shoreline Historical Museum’s “Agriculture / Grange / Nurseries / Artifacts” file. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, p. 42.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 17, 32, 62.

Bender, Growing Up With Lake Forest Park, pp. 258-260. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 13, 24, 27-29, 32-34, 40, 47, 48, 55, 58, 75, 83, 87-91, 100, 116-118, 128.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 19, 44, 76, 84. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 13, 90, 91.

- Clint Staaf and Syrene Forsman, “The Carlson Place,” Shoreline Historical Museum, unpublished manuscript, 1996.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 29, 47, 116, 118.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 7, 19. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 13, 27, 28, 32, 34, 40, 48, 55, 58, 75, 83, 87-90, 100, 116, 117.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 2, 4, 9, 44, 76, 84. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 13, 28, 55, 58, 83, 87-90, 116-118.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, pp. 7, 11, 44, 76. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 64, 75, 76, 89, 90.

Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 2, p. 68. - Worthley, Shoreline Memories, Vol. 1, pp. 90, 117.

- John Maier - Ridgecrest resident, verbal communication to author, 2003.

- Levi Pulkkinen, “Black Bear Spotted in Shoreline,” The Seattle PI, May 17, 2009, http://www.seattlepi.com/local/article/Black-bear-spotted-in-Shoreline-1304001.php (accessed December 14, 2012).

Neighbor / beekeeper, verbal communication to author, 2009. - Victory Gardens, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victory_garden (accessed December 14, 2012).

- Victory Gardens, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victory_garden (accessed December 14, 2012).

Staaf and Forsman, “The Carlson Place,” 1996. - Shoreline Historical Museum, personal interviews, Helen Cox Oltman, ND.

Shoreline Historical Museum, personal interviews, Bruce Adams, ND. - Victory Gardens, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victory_garden (accessed December 14, 2012).

- Shoreline Historical Museum, personal interviews, Helen Cox Oltman, ND.

- Shoreline Historical Museum, personal interviews, Bruce Adams, ND.

- “A Century of Change in America’s Eating Patterns - Major Trends in U.S. Food Supply, 1909-1998,” USDA Economic Research Service Publications, Food Review, Volume 23, Issue 1, January-April 2000

http://webarchives.cdlib.org/sw1bc3ts3z/http://ers.usda.gov/publications/foodreview/jan2000/frjan2000b.pdf (accessed December 2, 2012).

Calvin L. Beale, “A Century of Change in America’s Eating Patterns - A Century of Population Change and Growth,” USDA Economic Research Service Publications, Food Review, Volume 23, Issue 1, January-April 2000,

http://webarchives.cdlib.org/sw1bc3ts3z/http://ers.usda.gov/publications/foodreview/jan2000/frjan2000c.pdf (accessed December 2, 2012). - Diane Toops, “Food Processing: A History,” Food Processing, October 5, 2010, http://www.foodprocessing.com/articles/2010/anniversary.html?page=full (accessed December 2, 2012).

Interstate 5 in Washington, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interstate_5_in_Washington (accessed December 2, 2012). - Sharon Boswell and Loraine McConaghy, “Lights Out, Seattle,” The Seattle Times, November 3, 1996, http://seattletimes.com/special/centennial/november/lights_out.html (accessed December 3, 2012).

Back-to-the-Land Movement, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Back-to-the-land_movement (accessed December 2, 2012). - “History of the P-Patch Program,” Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, http://www.seattle.gov/neighborhoods/ppatch/aboutPpatch.htm (accessed December 3, 2012).

- Mark Musick, “The History of Seattle Tilth,” Seattle Tilth, February 12, 2008, http://seattletilth.org/about/abriefhistoryoftilth (accessed December 3, 2012).

- Brian Peterka, personal information.

Evelyn Nieves, “In downturn, cities grow fresh food where they can,” The Seattle Times, August 12, 2009, http://seattletimes.com/html/businesstechnology/2009643200_apusfarmsceneurbangardens.html (accessed January 10, 2013).

Richard Conlin, “Reflections on a Growing Local Food Movement,” YES! May 27, 2010, http://www.yesmagazine.org/blogs/richard-conlin/reflections-on-a-growing-local-food-movement (accessed January 11, 2013). - Brian Peterka, personal information.

DKH, “Meridian Park Neighborhood Association to Host Community Barter Nov 13,” Shoreline Area News, October 22, 2012, http://www.shorelineareanews.com/2012/10/meridian-park-neighborhood-association.html (accessed January 10, 2013). - Jenny Parks - Shoreline Children’s Center Garden, verbal communication to author, December 5, 2012.

Bonnie Chester - Shorewood High School Culinary Arts Garden, e-mail message to author, December 5, 2012.

Einstein Edible School Yard Program, The Edible Schoolyard Project, http://edibleschoolyard.org/program/einstein-edible-school-yard-0 (accessed December 3, 2012).

DKH, “Parkwood Community Helps Feed the Hungry,” June 27, 2011, Shoreline Area News, http://www.shorelineareanews.com/2011/06/parkwood-community-garden-helps-feeds.html (accessed December 3, 2012).

Judy Penn - Shoreline Community College Deep Roots Garden, e-mail message to author, December 4, 2012.

Joe Veyera, “New Community Garden Christened in Richmond Beach,” Shoreline-Lake Forest Park Patch, July 6, 2011, http://shoreline.patch.com/articles/new-community-garden-christened-in-richmond-beach (accessed December 3, 2012). - BALNA Community Garden, http://www.balna.org/ (accessed January 11, 2013).

RC Children’s Garden, http://rcchildrensgarden.wordpress.com/ (accessed January 11, 2013).

DKH, “Densmore Pathway project celebrates completion of first stage,” Shoreline Area News, October 16, 2011, http://www.shorelineareanews.com/2011/10/densmore-pathway-project-celebrates.html (accessed January 11, 2013).

“Twin Ponds Garden Plots Scooped Up By Residents,” Shoreline-Lake Forest Park Patch, March 22, 2012, http://shoreline.patch.com/articles/twin-ponds-garden-plots-scooped-up-by-residents (accessed January 11, 2013). - P-Patch Community Garden Program, 2012 Fact Sheet, Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, http://www.seattle.gov/neighborhoods/ppatch/documents/2012P-PatchSheet.pdf (accessed December 3, 2012).

- Constance Perenyi – Third Place Commons, e-mail message to author, January 12, 2013.

Shoreline Farmers Market, http://www.shorelinefarmersmarket.org/ (accessed December 3, 2012).